Local Hops, Local Wood, Local Beer, and a Place to Enjoy It

The Four Star Brewery in Northfield

Four Star Farms is a family farm in Northfield, owned and operated by the L’Etoile family. Under the stewardship of the current owners, this former Connecticut River bottomland dairy farm has grown and sold a variety of crops, including turf, specialty grains, nursery trees & shrubs, largemouth bass, and hops.

Four Star is one of the largest growers of hops in New England. A few years ago, the family made the decision to use some of the hop crop right on the farm and build a brewery. The result:

While the exterior of the building uses traditional lumberyard materials, the interior is an entirely different story. With species harvested primarily from farm field edges, the interior of the brewery showcases some of what can be done with available local wood.

Local contractors and businesses were used in every phase of the project. The landowner and a forester selected a variety of trees for harvest, based on size, species, accessibility, and interesting features. Species included oaks, maples, black cherry and hickory. Because they were field edge trees, they were somewhat open-grown and younger than typical forest-grown trees of the same age. Leo Lacwasan from Easthampton felled, bucked and forwarded the logs to a pile in a fallow field (Figs. 1, 2 & 3) formerly used for production of nursery stock.

The log pile was pretty scruffy, which created both challenges and opportunities. The hope was to get enough uniform product to provide flooring for the taproom, and to get a good mix of wood with interesting character, grain and “defects”, as well as some wide slabs for tables and a surface for the bar. Each log was sawn in the way that would yield best value for the interior of the building.

Matt Carruthers of Dummerston, VT was contracted to saw the logs into lumber, which he did right on the site, with the help of Collin Reid, one of the long-term seasonal farmworkers at Four Star. With a pickup and a medium duty trailer, Matt moved his tractor and Lucas sawmill to the site, setting up right next to the log pile.

After sawing, the lumber was trucked by Skip LeClerc from Northfield to Belchertown for drying in a vacuum kiln by Native Lumber. See Appendix for some detail on this aspect of the process. The oak flooring was manufactured by Ponders Hollow in Westfield, a custom flooring and millwork producer owned by the Lashway family. The family’s sawmill, Lashway Lumber, is located in Williamsburg.

Nathan L’Etoile, one of the owners of Four Star, made the slab tables, taking advantage of the widths, color, grain and defects of the slabs.

One of the really noteworthy features of this project is that each of the trees was sawed in a way that made best use of its characteristics, including the defects. Because no attempt was made to produce standard grades for a mass market, “defects” could become visually striking design elements for the building’s interior. Oak and maple were used for flooring, windowsills, tables and the bar; hickory was used for trim and the ceiling; cherry was used in the walls. And just about all the farm wood used in the building came from within a half-mile of the brewery.

Homework:

Visit the Four Star Brewery to get the full view of this superb use of local wood – and enjoy some local hops while you’re at it.

Appendix: Wood and Water – Always a Challenge

If you are doing anything with wood, water matters – ignore it at your peril. Wood contains a lot of water. The relationship between water and wood is complex. Some basics:

- In the growing tree, the amount of water varies by location in the stem and by season. But there is always a lot of it.

- Remember that wood is made up of several types of cells. Water in a tree is located primarily in two places: inside the cells of wood (“free water”) and in the cell walls that separate one cell from another (“bound water”). Free water is easy to remove from a piece of wood; bound water is held in a more complex way.

- At any point in time, water is not held uniformly within a log or piece of lumber. Atmospheric conditions will affect the ends and the exterior of a log or board more and sooner than the center. Water to be removed from the center must move first toward the ends and the outside surface.

- Wood is “hygroscopic” – it takes up and can retain moisture from the air. This is a dynamic process and the amount of water in a piece of wood will vary as relative humidity changes. Even in service when seemingly stable, wood remains hygroscopic. Think of that window or door that sticks in July, but not in January. At any point in time, wood can reach an equilibrium state where it is neither gaining nor losing water – this is determined by the relative humidity in the immediate environment.

- Wood changes in dimension when bound water is removed. Wood does not dry at the same rate along its various dimensions: longitudinal, tangential (parallel to growth rings), and radial (perpendicular to growth rings). For some uses of wood (e.g., firewood), we don’t care about the “checking” that results from uncontrolled drying. However, for higher end uses, such as furniture, flooring, and cabinetry, drying has to be controlled to produce a stable in-service result.

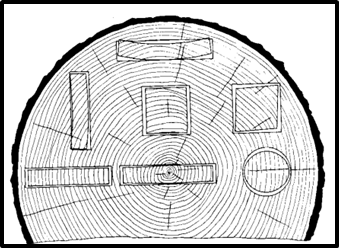

- The log cross-section below shows the effect of location on the drying stresses that need to be controlled. Note how the shape of the original board can change as it dries, due to the position in the log and the relationship to the growth rings (parallel or perpendicular).

- Much of the lumber that is used in places like the Four Star Brewery is dried in a kiln to control the rate of drying and the resulting stresses and shrinkage. There are several types of kilns (conventional, dehumidification, vacuum, and others) but the principles of drying remain the same. Air circulation, humidity control, and temperature are the key variables. Water has to be removed from the wood at a controlled rate to achieve the target moisture level without stressing the wood to the point of warping, checking, cupping, or causing other problems which will degrade and devalue the wood. The recipe or sequence of drying steps (“kiln schedule”) varies according to species, board thickness, and final moisture content. Vacuum kilns, such as the one used to dry Four Star’s wood, are pretty uncommon. They are quite expensive to buy, but are able to dry small quantities of valuable and specially sized wood, very quickly and with high quality results. The basic principle of a vacuum kiln is to lower the boiling point of water by creating a vacuum in the drying vessel. This often means that wood can be dried in days, rather than weeks or even months.